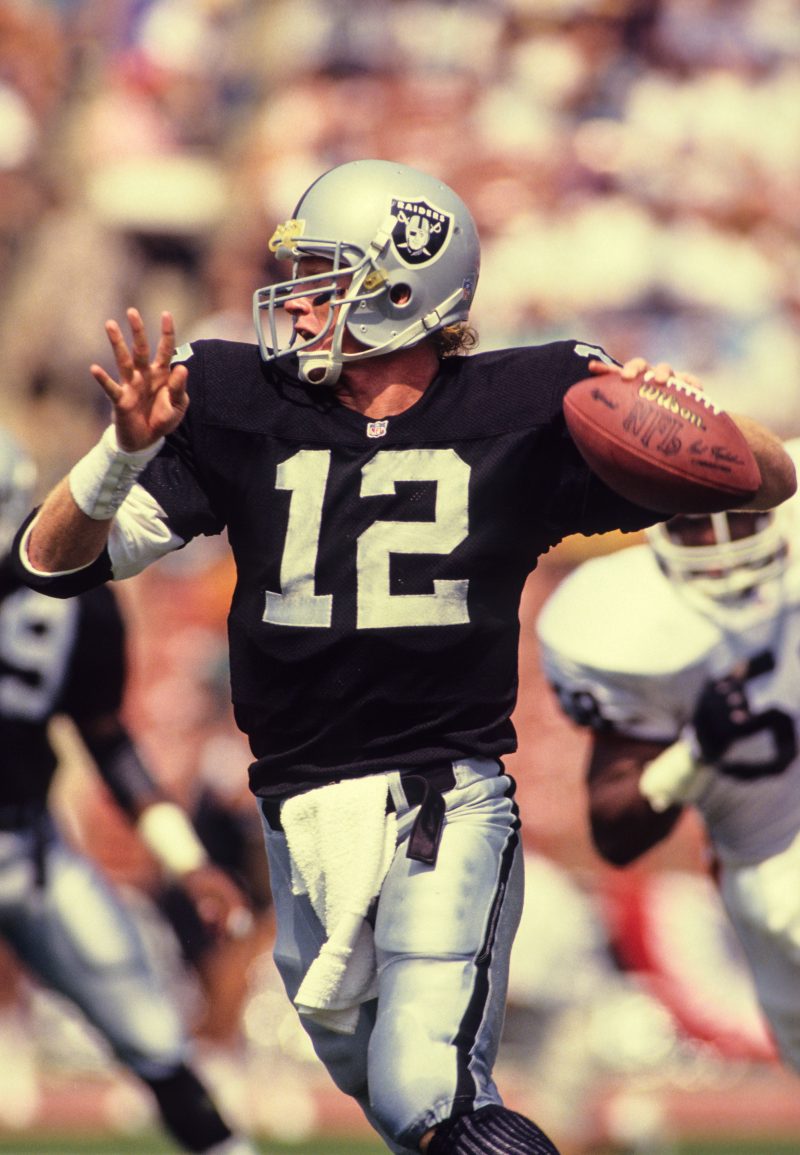

- Todd Marinovich, subbed ‘Robo QB’ by sportswriters, played college football at USC before being a first-round pick of the Los Angeles Raiders.

- Marv Marinovich, one of the original ‘worst sports fathers,’ put Todd through rigorous daily training sessions as a child.

- “Marinovich: Outside the Lines in Football, Art, and Addiction” is Todd’s effort to tell his well-chronicled story in his own words.

Marv Marinovich was one of the original “worst sports fathers,” decades before the obsession with young athletes spilled over to social media, years before there was even an Internet.

‘I didn’t make it through a full tackle football season until high school,” Todd Marinovich, his father’s prodigy turned USC quarterback and Los Angeles Raiders first-round NFL Draft pick, recalls in his new memoir. ‘Why? Marv bodychecked my coaches when he disagreed with their decisions.”

His father, Marinovich told USA TODAY Sports, “did not miss a (expletive) practice in any sport I played, from youth until I went to SC.”

It was Marv who caught flak from in-laws critical of punishments such as forcing the 9-year-old Todd to run alongside the car from Huntington Beach to Newport Beach after the boy had not played his best in a basketball game. Sportswriters call his son ‘Robo QB” and ‘the first test-tube athlete.‘ … Parenting authorities say his methods signal an abhorrent and dangerous trend among upper- and middle-class parents: over-programming their children and depriving them of childhood. Child-rearing experts say ‘hot housing,’ or the forced maturing of young children, has become a frightening national trend in academic and social life as well as sports.

— Los Angeles Times, June 17, 1990

The process of ‘letting go” has been cathartic. Marinovich met once a week with co-author Lizzy Wright. He shared his story of soaring to the NFL after his college sophomore year and his downward spiral out of it with drug abuse. He is at peace with ‘Marv,” the father he called by his first name.

A term of affection? ‘There’s probably some deep psychological or subconscious thing that I might have been doing, but it truly was,’ Todd says.

Their relationship was complicated: The every day (even Christmas) football training routine, the hand signals from the bleachers, the healthier ‘Marv-sanctioned” versions of cake and ice cream he had to bring to birthday parties while other kids ate the real thing.

Todd became a father of two who now manages youth football, and fatherhood, in a completely opposite way and with deep perspective.

‘The most challenging endeavor of my life is being a parent,” he says.

USA TODAY Sports spoke with him about what young athletes and their parents can learn from his story.

Pull out the good you remember from your parents and coaches

‘Marinovich: Outside the Lines in Football, Art, and Addiction” is Todd’s effort to tell his well-chronicled story in his own words. It’s through the eyes of a father to Baron, a sophomore in high school, and Coco, a freshman.

Baron plays quarterback, and also receiver, the way Todd started out.

‘What’s really cool about having a son and a daughter is they get to have their own experience with the game,” says Todd, now 56. ‘It’s beautiful, and it’s not always fun.

‘I just am a huge fan of team sports, where you learn that it’s not about ‘me.’ My son’s getting his own experience that’s so different than mine, and I just get to be a spectator and watch it. It’s hard not to want to get too involved.”

He laughs heartily.

‘I know,” he says. “Marvisms are coming up left and right when I’m teaching. … But being on the other receiving end of that kind of coaching, I just try to emulate my favorite coaches all in one, and they all had something special that they did that affected me as a player.”

Marv had been a football captain at USC in 1962, and he played ever so briefly in the NFL, before his body broke down. He moved on to breaking ground as an NFL strength and conditioning coach.

And he set out to make his son a perfectly engineered athlete who was ahead of his time. Squats and shamrock shakes (“swamp water,” Todd thought as he digested them before a youth game) were a must.

It was Todd against the world, entangled in an endless loop of ‘Bull in the Ring,” a training technique Marv particularly loved where two football players grapple like Greco-Roman wrestlers.

“It’s a great drill,” Todd admits, “and you find out really quick who your players are.”

He found himself using it in recent years when he volunteered to coach football at a local high school on Hawaii’s big island, where he lives now.

But Todd’s team practiced for an hour and headed to the beach. He took a similar approach when he coached in a kids flag football league.

‘I don’t go more than 40 minutes because I can’t concentrate for more than 40 minutes,” he says. “How am I gonna expect a 10 year old to stay with me for 40 minutes? I don’t understand when my son calls me and says they’re out from 2 to 6, on the field. What the heck? I mean, come on, guys.

“You’ve gotta make it fun and throw in some coaching along the way. So many coaches ruin high school experiences or even youth where the kid doesn’t want to do it again, because it’s no fun. So I try to be super encouraging because you can always find something, even if they’re new to the game, that they’re doing right.”

IT’S THE FALL SEASON: Here’s how we reset as youth sports parents

It’s easy to treat kids as adults and expect too much, too early

The way Todd breaks down Marv today is similar to how Andre Agassi describes his own autocratic sports father: It’s as if dad loved them so much, it turned into obsession.

When Marinovich reached high school, he became starting quarterback at nationally-renowned Mater Dei High in Santa Ana, California, as a freshman. When he told his father the news, he saw something that loosely resembled a smile.

Writes Todd: ‘He wouldn’t say he was proud, but I knew it.”

‘People tagged him for all kinds of things of just being like that stage mother,” he tells USA TODAY Sports. ‘That’s what he was passionate about, training athletes, and football was the vehicle for a while. And so I was just immersed in it. That’s what the family did. It was just part of our culture. So did he influence that? Yeah, but he wasn’t like, ‘You gotta play this.’ If I just wanted to do basketball, he would have been fine with it. He just wanted me to perform at a high level and train.

‘It wasn’t, truly, about living through me, like some people have said because he never did much in the NFL. It was none of that. I have always known that he wanted the best for me. He did the best he could at the same time. Did I agree with some of it? No, but that’s part of growing up.”

When he was 10, Todd opened the garage (the fitness “dojo” as he called it) and found Marv explaining the day’s training regimen with four Los Angeles Rams players.

They called him Marv and they got excited when they said it. Todd loved feeling close to dad, so he tried it, too.

‘Hey, Marv.”

Everyone paused, Todd feeling palpable tension before his father broke out in laughter.

‘Okay, Red Rocket, you can call me Marv too.‘

‘The thing that I seem to be able to do that my dad couldn’t is know appropriate for the age,” Todd says. ‘He was working for like an All-Pro, eight-year veteran and a nine year old. There’s just no difference with the way he used to do it.”

Marv told a 2011 ESPN ’30 for 30” he stretched his son’s hamstrings in the crib. Todd said he could probably run 4 miles at four and 10 miles at 10.

When he didn’t perform well, though, he felt family life held in the balance.

Traci, his older sister, remembers being in the car on a disciplinary run home. His mom, Trudi, didn’t have the courage to tell Marv how she felt about what their life had become.

One weekend, Trudi wrote him a brief note and whisked their son away to San Diego, where Todd had ice cream, beach time and freedom.

“She just knew when I needed that break from Marv,” Todd says. “And throughout my struggles, she’s just been that unconditional love. It’s a mother’s love, and I put her through some sleepless nights, I know that. And my amends to her is trying to live right, and she’s been there. Thank God. I’ll tell you what: I don’t think I would be here (without her).”

Don’t let your teammates down, it’s not about ‘me’

Todd felt that freedom playing basketball, too.

‘You’re in range when you step in the gym,” Gary McKnight, his middle school coach, would tell him. “And if you don’t shoot, I’m sitting you down.’

‘Within his constructs, you could really have fun,’ Todd says. ‘It wasn’t my main sport. It was more I’m just doing this for fun. And when you’re in that state, you tend to perform better.”

The team became a machine, he says, going 177-7 over three years.

McKnight played to strengths and gave everyone a distinct role. You tried not to step out of it.

Leaning on other people would become a consistent theme in Todd’s life, through all the turmoil yet to come from USC to the Raiders to rehab.

“In an undercover way, I was getting these fundamentals or principles ingrained,” he says. “You realize that’s what it’s about. It’s not about me. When I start getting into me, I am completely (expletive). Every time. But if I’m thinking about the guy next to me, not wanting to let them down, and showing up, that whole thing about showing up, you show up, no matter what. There’s no calling in sick. That doesn’t exist. You cannot do that because they got doctors there. So that’s just priceless stuff that you only learn through time.

“I thought when I was doing it, it was about winning.”

Win, he did, at Capistrano Valley High, where he transferred and set a then-a national record for passing yards; at USC, where he won a Rose Bowl; and even with the Raiders for a fleeting moment over a small stretch.

But when he looks back on his career, he thinks more about the guys with whom he spent it.

Among many others, there was Jeff Peace, the linebacker from a rival high school Todd went against when they competed for a league title. “He just snuffed me,” Marinovich says. They became roommates at USC and are still tight.

There was Marcus Allen, the Hall of Fame running back and Raiders teammate who roused him from bed the morning after another bender with ecstasy, cocaine and liquor and got him to practice.

And there was Marv.

The spirit of a coach/parent lasts a lifetime

Father and son lived together, alone, when Todd’s parents separated as he played at Capistrano Valley. It was Marv without emergency brakes, as Todd put it, and a period where he was a budding addict.

At USC, the quarterback was under the care of Larry Smith, an old-school coaching assistant to Bo Schembechler at Michigan.

‘He got a hard package to handle,” Todd says. “It’s not that way anymore, but any authority really was Marv. So when I left Marv, Larry became Marv. Larry was trying to tell me what to do, like, cut my hair? Well (expletive) you. You can’t wear sandals? I was over the ‘Yes, sir, no, sir,’ and it just happened, and Larry had come from that kind of background in the Midwest. It was the army, pretty much what you were in. That was like the furthest thing that I wanted the game of football to be.

‘I just thought it was definitely more creative and free spirited than that. So it was a volatile time that second season. It just came to a head.”

The two erupted in an argument on the sidelines captured on television at the 1990 Sun Bowl after an up-and-down season. It was decades before the transfer portal.

‘I was enjoying my college experience,” Todd says. ‘I did not want to do the NFL as a sophomore. I just felt like that was my only option.”

A month later, he was arrested for cocaine possession after a long night of revelry with his buddies. His first two experiences with rehabilitation came when he was still with the Raiders.

“I was winding down as my career was going up,” he says.

When his NFL career ended after eight games over two seasons, he faced more arrests and rehab stints. Father and son had drifted apart when he left for USC. But eventually, they found themselves back together.

“Even as hardcore as he was, he was always in times of doubt … there to give me that quiet confidence of, no, I do belong here, and yeah, I can overcome,” Todd says, “and throughout my whole journey, being strung out on heroin, he was there, saying, ‘You can do this.’”

Toward the end of his life, Marv, who died in 2020, had Alzheimer’s. Father and son lived together for long stints.

Over nearly 16 months, Buzzy, as Todd then called Marv, brought a wood sculpture to life, while Todd painted nearby. It was Todd’s turn to provide support.

‘It’s just crazy being on the other end of this illness,” Todd says. ‘It’s just bizarre, but I’m so grateful that I was there. If I would have done what I wanted – my head said just run from that because he’s not the same person – I would have missed lots of just priceless (moments). Because it was all about the now. We weren’t talking about yesterday; that’s gone with that illness. It’s just locking into the now and enjoying each other.”

It’s how he approaches life as he paints for a living in Hawaii. He talks to his son, Baron, who plays at Costa Mesa High in Orange County, after practices and games.

He bonds with his daughter, Coco, over art, his new life’s passion. It was their mother, Alix, his wife at the time, who suggested he paint.

“I find that place in creating art where time is nonexistent,” he says. “I felt similar coaching. And that’s a beautiful thing. That’s a sweet spot that I try to be in as much as possible.”

He steps into painting, and he never knows how long he’ll be there. Sometimes 10 minutes, sometimes 10 hours. Either way, he says, there are no shortcuts.

It’s a lesson he learned from football, and from Marv. He uses a different name this time.

“Dad really flourished into like a best friend toward the end,” he says. “It was really an amazing journey with him.”

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.